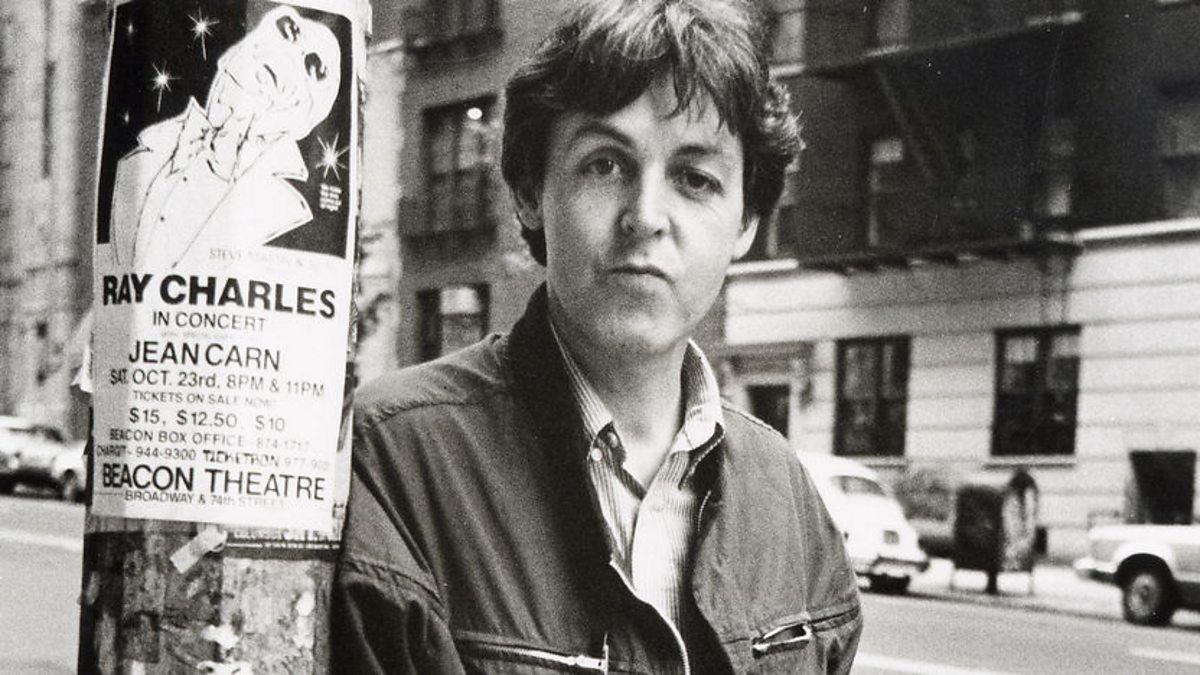

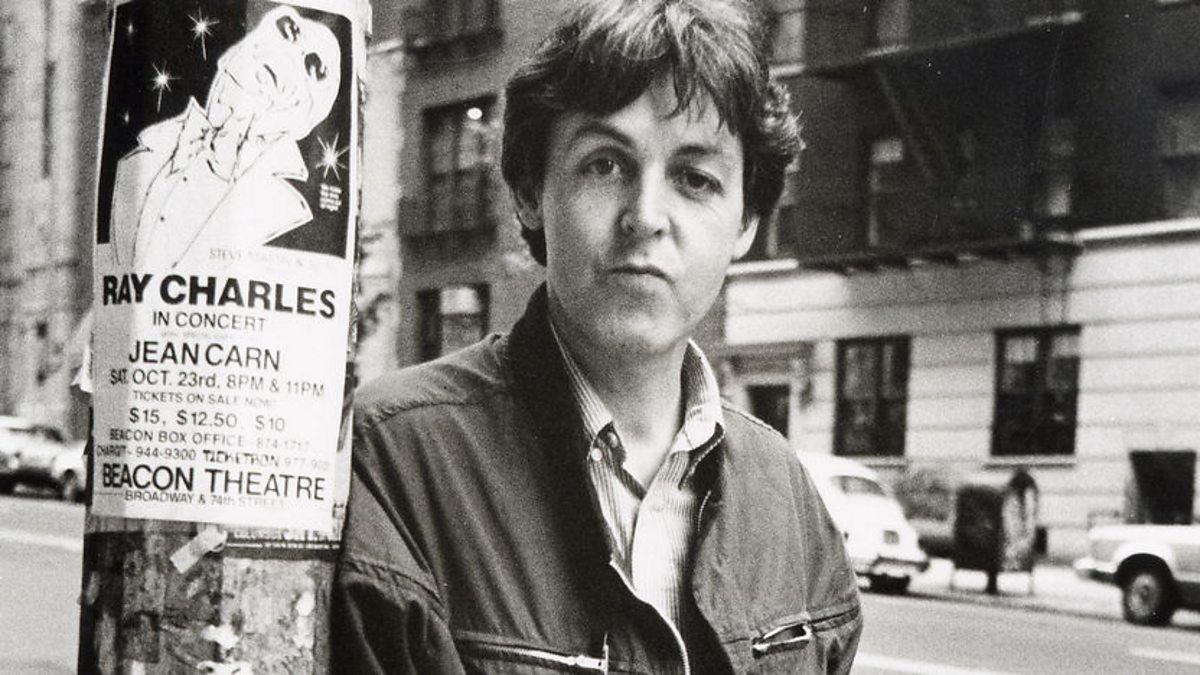

ABOUT THIS INTERVIEW:

In their April/May 1982 issue, the Canadian music magazine Music Express featured an exclusive interview with Paul McCartney. Ray Bonici chatted with Paul about Denny Laine and the breakup of Wings, the Beatles, John Lennon's death, and Paul's forthcoming LP, Tug Of War. The album was released on April 26th. The Music Express article was entitled, 'Paul McCartney Wings It Alone.'

- Jay Spangler, www.beatlesinterviews.org

Starting off, I want to congratulate you on your third studio album, Tug of War.

Paul: Thank you.

First question, does Wings still exist? Considering this is your solo album.

Paul: No, not really. We sort of disbanded for this album. If we're going to pick it up again we should just be loose enough to come together again or not. You see, I hate the pressure of a group.

But you were in The Beatles, so you've done it before.

Paul: Yeah, I did it. That's right. I did it with the Beatles. Towards the end there was a bit of a pressure but I never really felt it. I just felt the positive side of the group. But with Wings, with so many changes in the line-up, it wasn't so easy. That often distracts you from the music and you start thinking a whole load of other things. You're thinking about the group image. Anyway, I got bored with the whole idea and I thought, 'Christ! I'm coming up to 40 now. I don't really have to stay in a group. There's no rule anywhere that says I have to it that way.' At that time Denny Laine was staying with me. We were writing together. He was going to stay on but we had a bit of a falling out. It was nothing madly serious, but he did decide to go his own way, saying that he want to go on tour. He hasn't been on tour since... (laughs) However, he wanted to get his own thing together.

It seems that there was definately a hatchet floating about and that it wasn't buried as you had said. The arguments are still there.

Paul: With Denny? There were little personal things here and there, little things that were just niggly. In the end it blew up a bit. It was a bit of a number. We didn't part shouting at each other or arguing. We both decided that it would be best... in fact, it was his own decision. I can never remember these things because once they're gone they're gone. It was his decision. He rang up saying that he was going out on his own to get his own stuff together. He thought he'd be happier that way. I just said OK and kept on with this album. Seeing I was doing it this way, working with other people, there wasn't the normal big trauma: 'What? Somebody hasn't turned up? Oh God!' Or, 'Are the lights here?' 'Yeah, but the drummer isn't!' Panicky stuff. You just spend all your time worry about that. I decided that all I really am interested in is the music anyway, and not in huge personality things.

You are the only one who went back into a group after the Beatles. John, George and Ringo did their stuff with other musicians. Now you're doing it for the first time. Do you regret not having done this earlier?

Paul: Yes. It would probably have been a good thing to start it then. At the time I felt that it was a bit too predictable, that everyone would leave the Beatles and go with old Phil Spector or the drummer, Jim Keltner. It was like a clique and I just didn't want to join that clique. The decision I made was mainly to get the group together to play with because, with the Beatles, we weren't really playing alot. I thought of doing that after I had seen Johnny Cash on TV and I wanted a similar group with a couple of guitars and drums just to have sung with. That's what I did.

I heard there was an incident in 1968 involving Ringo, do you care to give any details on that?

Paul: It was a very short, brief thing, Ringo came to us one day and he said he'd put someone in hospital. Next thing you know, he's dead. It was incredibly brief and I don't remember much about it.

You don't remember that much about it?

Paul: It's not something the group like to bring up, Ringo never talked about it besides that whole panicky 'I've killed someone!.' Then again, much of us don't like to think about those days ... it's just gone from my mind completely. For the best.

I understand, on with other things. Lets go back to Wings now. Are you splitting from Linda musically?

Paul: (Laughs) I like that. No. In fact, she did the harmonies on this album. The thing was just getting musically limiting so I did say to Linda, 'Look, if I wanted to use some other people on harmonies, how do you feel about that?' She said okay. As it happened, we did it ourselves-- together with Eric Stewart.

What's easier-- dealing with Linda the musician or Linda the housewife?

Paul: Linda as a musician is easy. She's easy because she'll do what you want and she's not that much of a creator. On this album George Martin and I wrote the harmony parts out for her. Linda as a housewife? Well now, that's emotional. That's real life. That's not as easy as music. I love it. I love it. I wouldn't change a thing. But it's hard work. It's hard graft.

Just like other married people?

Paul: Yeah. And you don't even have to be married. You might be living in a house with just one other person. That's what difficult. Relating to people. I don't know how I would compare against anyone else, or how Linda would compare against anyone else. Listen, the truth is, we have our ups and downs like everyone else. Sometimes it's just so terrific you wouldn't believe it. Sometimes we're rowing. That seems to be the story with most homo sapiens.

Was Linda the person who 'came in through the bathroom window?' John said she was.

Paul: No she wasn't. Well, John-- what does he know? (laughs) This is the joke. He doesn't know any more than I do or anyone else does. He's gold, John. He was great, a fabulous guy and a beautiful person but he didn't have a monopoly on sense. He was as daft as the next man. He could make his mistakes too. I don't know. She may have been. I wrote it round about that time, but I didn't consciously think, 'She came in through the bathroom window.' Alot of the time when I do songs like that, it's just because the words sound good. You can get stuff which makes great sense but which is not good to sing. It doesn't flow well. The words aren't right.

What about live shows? Are you going to perform live? You said after John was killed, 'For security reasons we reckon we shouldn't play live.'

Paul: Yeah. That was right after the John thing. That was my response at that time. I'm obviously thinking about all that wondering if I want to. And really, I'll be the same as I've always ever been: if the idea grabs me I'll do it until I don't want to. I'm definitely not thinking I won't ever do it again. Sometimes I really miss performing. I don't at the moment because I'm doing so much work on the album. I am performing, only in a studio. Then after this album, I'm trying to put a film together. Isn't everyone? But mine's different. Mine is better. I'm trying to get a film based on this album, so that will take care a bit of time. I suppose after that I might perform. I'd just go and do it. You can't worry about your security all the time.

You're not terrified now?

Paul: No. I was very terrified right after John's death because it's such a horror for such a thing to happen. I was talking to Yoko about this-- I had a few conversations with her quite recently and she told me people don't like me because of certain things I've said. For instance, when John was killed I was asked for a quote. I said, 'It's a drag.' To me, looking back on it, I was just stunned. I couldn't think of anything else to say. I could have tried for a sentence and put it all into words. I couldn't. It was just like 'blob, blob, blob.' All I said was, 'Ah! It's a drag.' (pauses) That, put in cold print, sounds terrible: 'Paul's reaction today was, It's a drag thank you very much, and then he got into his car and zoomed off.' That's the terrible thing about all that stuff. That's the PR thing again. I hate all that because I don't ever mean it like it comes out in print.

Were you actually still close to him?

Paul: Yes, yes. I suppose the story was that we were pretty close in the beginning when we were writing stuff together. We felt alot of sympathy for each other, although on a personal level, based on a lot of stuff that went down later, I obviously wasn't that close to him. To me, he was a fella, and you don't get that close to fellas. I felt very close to him, but from alot of what he said later, obviously, I was missing in the picture. But anyway, I felt very close to him then and when the Beatles started to feel the strain towards the last couple of years, it was getting to be a bit of a strain and we were drifting more apart. I think the kind of anchor that had held us together was still there. I think that we all, in a way, started to get really angry with each other, annoyed and frustrated, but we were still very keen on each other, loved each other, I suppose, because we had been mates together for so long. Like Ringo says, 'We were as three brothers.' It's that kind of a feeling. I mean, I didn't realize that, but Ringo would tell me later, 'You are like my brothers, you lot.' We all knew that there was some kind of deep regard for each other.

When the rift started, it was more like a divorce, like a love/hate relationship, coming apart. Is that true?

Paul: Yes. It sounds weird when you use that analogy because then it takes on another meaning. But yes, it's true. What I mean is that there was that kind of deep feeling and deep heat. (laughs) Then we started arguing about the business and we just started to drift apart, as you say, like a kind of divorce. The bitchiness set in and everyone started going, 'Oh you say that, do you? Well, I'm really gonna let you know what I've been thinking all these years.' And we tended to go over a little bit over the top, I suppose. So it started to split apart. We got very estranged because John went to live in New York with Yoko and they were very much their own couple and there weren't many people that could get into that thing. I really think that was one of the best things that ever happened to him, for his personal happiness. It wasn't too easy for all of us, because he was sort of leaving us and going off on a new life and, whether you like it or not, we felt that each one of us had been each other's crutches for a long time. Then, with John moving away, there was a lot of bitchiness carrying on. I talked to Yoko the day after John was killed and the first thing she said was, 'John was really fond of you, you know.' It was almost as if she sensed that I was wondering whether he had... whether the relationship had snapped. I believe it was always there. I believe he really was fond of me, as she said. We were really the best of mates. It was really ace.

George Martin said there was a possibility that you and John would work together again.

Paul: Yes. I don't know what would have happened. It had loosened up a bit. It's loosened up more now and I'm talking to Yoko. And we're really talking.

Which seems strange to the public, you talking to Yoko.

Paul: Yes, but I don't know why it should seem like that. I tell you what, it seemed strange to me. She's a very tough lady and John and she made a very formidable couple and often I'd talk to them and they made me fearful. I rang her up two or three weeks ago and I said, 'Look, I'm real nervous about making this phone call.' And we immediately owned up. We really started owning up with each other and she said, 'Well, you're nervous? You're kidding! I'm more nervous than you!' That really helped. It's good to be open with each other, but I've never been the most open to people. That's what I like about New Yorkers and American people... they are very blunt. It's all 'afternoon' analysis anyway. Well, Liverpudlians are, too, but I've not been particularly blunt. It's no big hang-up for me, but nowadays I like being a bit more real -- telling people the truth behind the story. They have more sympathy with you and you find more sympathy with others.